Letter from Haiti: The Vives Exhibition at the Maison Dufort

During my stay here in Haiti, I have had the opportunity to share a house, and to work and exchange thoughts with two highly accomplished women in the arts of the Caribbean: Miriam Hinds-Smith, the Dean of the School of Visual Arts at the Edna Manley, who is on sabbatical this year and on an artist’s residency at Le Centre d’Art, and Régine Cuzin, a Paris-based independent curator, art historian, and art book editor who is best known for her work in and about the Francophone Caribbean.

Cuzin’s best-known project is Haiti: Two Centuries of Artistic Creation (2014-2015), a 150-work survey of Haitian art history which she co-curated with the Haitian gallerist Mireille Pérodin Jerome and which was shown at the Grand Palais in Paris. During our shared time, it was evident that her involvement in Haitian art is deep and well-informed, and well-respected in Haiti. Her thoughtfully and imaginatively conceived exhibitions and writings transcend the troubling representational problems that have plagued that field, such as the reductive perception that the only part of Haitian art that matters is the so-called “naïve” school of self-taught painters and sculptors.

Régine Cuzin was in Haiti as the curator of the Vives exhibition, an exhibition of women’s art from the collections of Le Centre d’Art and the Musée d’Art Haitien. The exhibition was commissioned as part of the Quatre Chemins theatre festival, an annual event in Port-au-Prince, organized by the Haitian playwright, director and actor Guy Régis Junior, and was presented in association with Le Centre d’Art. The theme of this year’s festival, which was held in November 2021, was “Who is Against Equality?”, a pertinent and generative question in the current local and global environment. The accompanying art exhibition, Vives, was, for organizational reasons, postponed to January, and presented an interesting coda to the questions asked in the last year’s edition of the festival.

The recently closed Musée d’Art Haitien du College de St Pierre, a small museum in Port-au-Prince was established as a private initiative, with the support of Le Centre d’Art and other partners, and held some of the most iconic works of Haitian art. Conditions at the museum had deteriorated since the 2010 earthquake and the collection was recently handed over to Le Centre d’Art for safekeeping and conservation (there is an active conservation programme, with support from the Smithsonian and the École du Louvre). When Le Centre d’Art moves to its new, significantly expanded premises at the Maison Larsen in a few years, there will finally be space for permanent and temporary exhibitions that do justice to the breath and depth of Haitian art history and, importantly, that are consistently available to audiences in Haiti. The Vives exhibition is, in fact, a first step towards establishing a regular exhibition programme with selections from the collections of Le Centre d’Art and the Musée d’Art Haitien, and a few loans from artists who have more recently been associated with Le Centre d’Art but who are not yet well represented in the collection.

Vives may not be the first exhibition of art by women artists in Haiti, but it may well be the first one to provide an historical overview of work by women artists who have been involved with Le Centre d’Art from the 1940s to the present. It is an important intervention into the gender politics of the Haitian art world, which has traditionally been male-dominated, with women relegated to “supporting cast” roles, as arts administrators and dealers, and presumed second-tier artists. In fact, the entire official historiography of Haiti strongly favours the “big man”, such as the male leaders of the Haitian revolution. At the MUPANAH national history museum, a few women are mentioned in a tribute wall with names of persons who have played key roles in Haitian history, but none are given any prominence in the exhibits. In the dominant narratives on Haitian art history, likewise, the assumption is clearly that “the artist” is a man (and furthermore, a painter, but that is another matter).

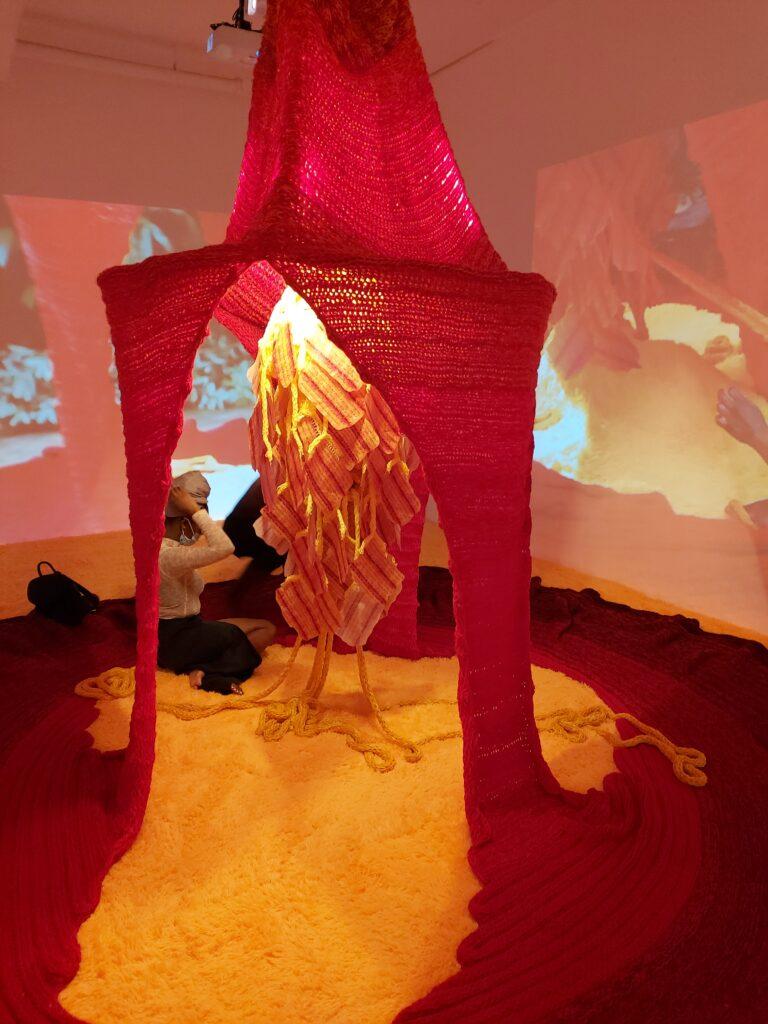

This masculinist bias in the Haitian art world has been successfully challenged by contemporary artists such as Barbara Prézeau, Pascale Monnin, Mafalda Mondestin or Tessa Mars, who have gained significant local and international critical recognition. In fact, Tessa Mars’ avatar Tessalines, which appears in many of her works, is a playful but pointed challenge to the masculinist bias in Haiti’s national narratives, with reference to the revolutionary hero Jean-Jacques Dessalines.

That there is so little information on some of the artists in the exhibition, such as a self-taught artist known only as Madame Henry, points to the extent to which female artists have been traditionally ignored in the documentation and articulation of Haiti’s art history, and the urgent corrective art-historical and curatorial work that needs to be done. It needs to be recognized that most of those female Haitian artists who have historically received some recognition, such as Luce Turnier, came from more privileged backgrounds, an often-unacknowledged class dynamic in women’s art which is seen throughout the Caribbean. But even Turnier, a distinctive and compelling modernist voice among the Haitian artists of her generation, deserves far more recognition than she has thus far received. There are no Edna Manleys in the Haitian art world.

To frame the work of female artists as “women’s art” can be problematic, however, as not all female artists wish to be defined in such gendered terms. Many just want to be recognized as artists, without being constrained by any imposed assumptions about the nature of their work. The Vives exhibition, fortunately, does not make such pronouncements and is instead deftly and sensitively curated to allow the selected work to speak on its own terms. It is an exhibition in which the imagination rules and visual poetry is given full reign. An albino crocodile is whispering in the ears of a young girl in a dream-like image in the painting Chuchotements (2014) by Pascale Monnin, leaving us to wonder what the enigmatic murmurings are all about.

Many of the works in the exhibition do speak to gender issues and several talk back to oppressive gender dynamics in ways that are subtly humorous and subversive. The elusive Madame Henry’s Two Women and a Men, for instance, portray a diminutive man who is almost obscured by the two female figures in front of him, speaking to those de facto matriarchal dynamics in Caribbean families that represent a much-needed challenge to the entrenched patriarchies. This subtly subversive spirit is carried over into the curation of the exhibition, such as the juxtaposition, on two opposing walls, of Barbara Prezeau-Stephenson’s languorous reclining male nude, which flips the script on the typical “male gaze” on the female body, and a tautly delineated sleeping female nude by Luce Turnier, in which the figure appears turned inwards, in a moment of psychological marronage, and unavailable for any objectifying visual consumption.

The Vives exhibition is beautifully installed in the historic Maison Dufort, working with rather than against the monochromatic, elegant aesthetics of its interior architecture. A salon-style wall of works on paper, all beautifully presented behind plexiglass mounts (which were impeccably fabricated locally) adding to the multi-layered visual and thematic dialogues in the exhibition but also giving these prints and drawings a compelling presence of their own, against the more visually assertive statements made by the paintings. I often collaborate with other curators, but I only rarely get a “behind the scenes” view of a curator who is working on an exhibition that does not as such involve me. Seeing Régine Cuzin at work, making exhibition sense of a diverse group of works that she had originally selected from digital reproductions in what is an inspiring but challenging setting, was indeed a master class in curating.

Dr Veerle Poupeye is an art historian specialized in art from the Caribbean. She lectures at the Edna Manley College of the Visual and Performing Arts in Kingston, Jamaica, and works as an independent curator, writer, researcher, and cultural consultant. Her personal blog can be found at veerlepoupeye.com.